Preface

The Editor

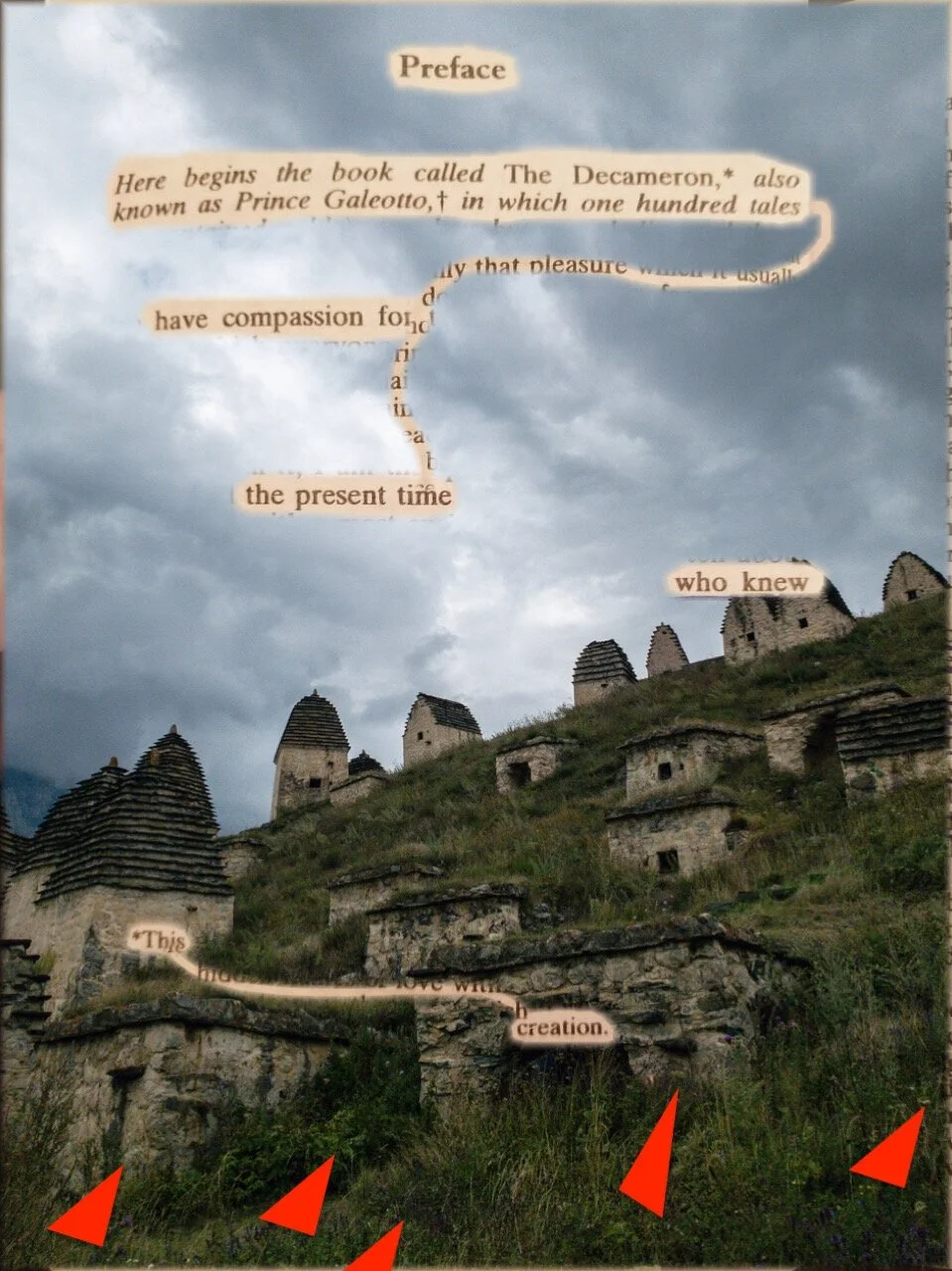

Here begins the book called The Decameron,* also known as Prince Galeotto, in which one hundred tales have compassion for the present time. Who knew—

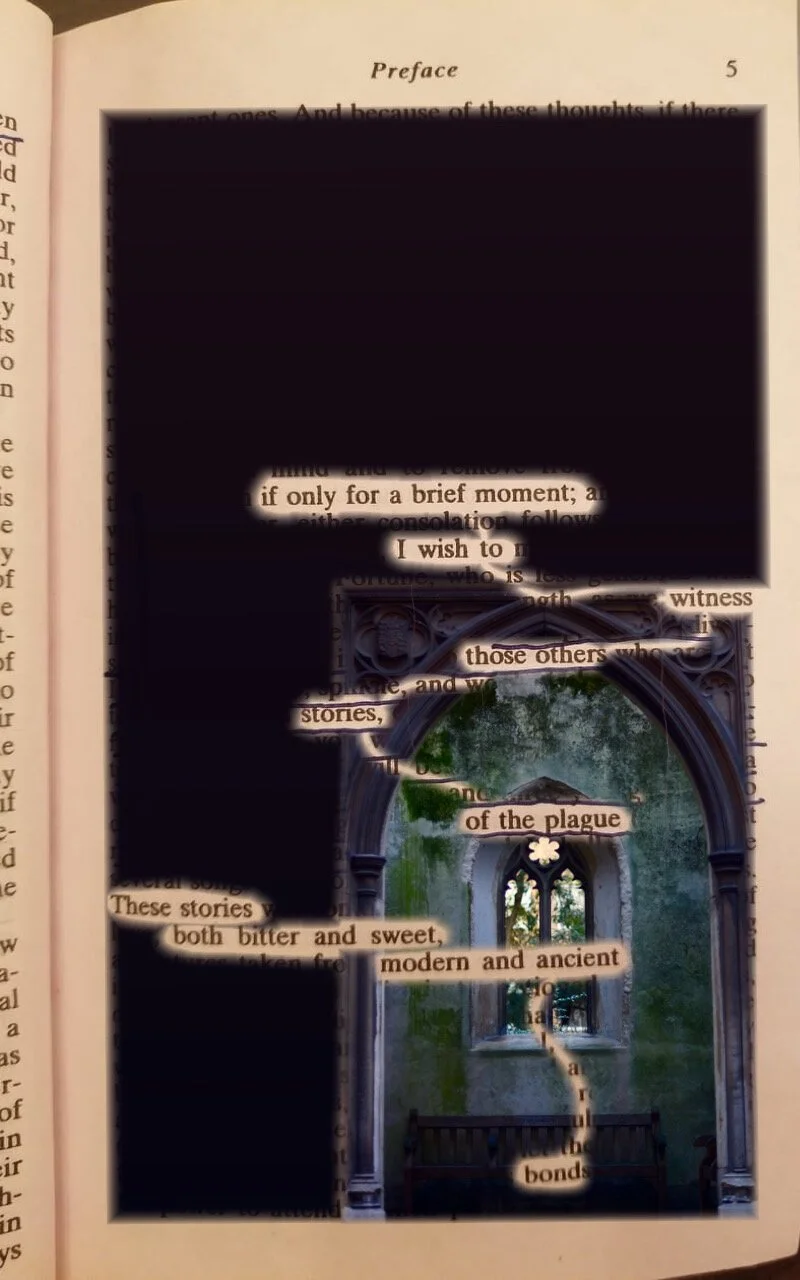

If only for a brief moment, I wish to witness those other stories of the plague. Stories both bitter and sweet, modern and ancient, bond—

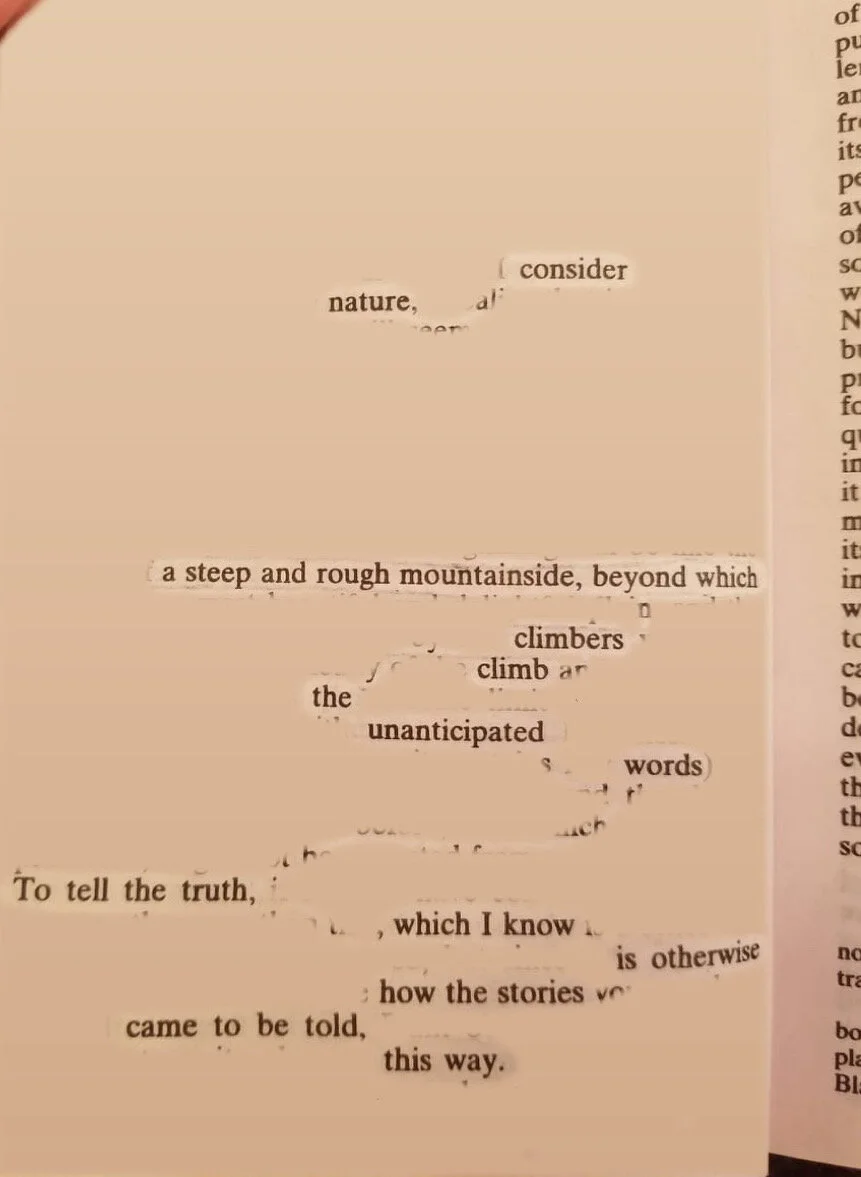

Consider nature: A steep and rough mountainside, beyond which climbers climb unanticipated words to tell the truth, which I know is otherwise how the stories came to be told this way—

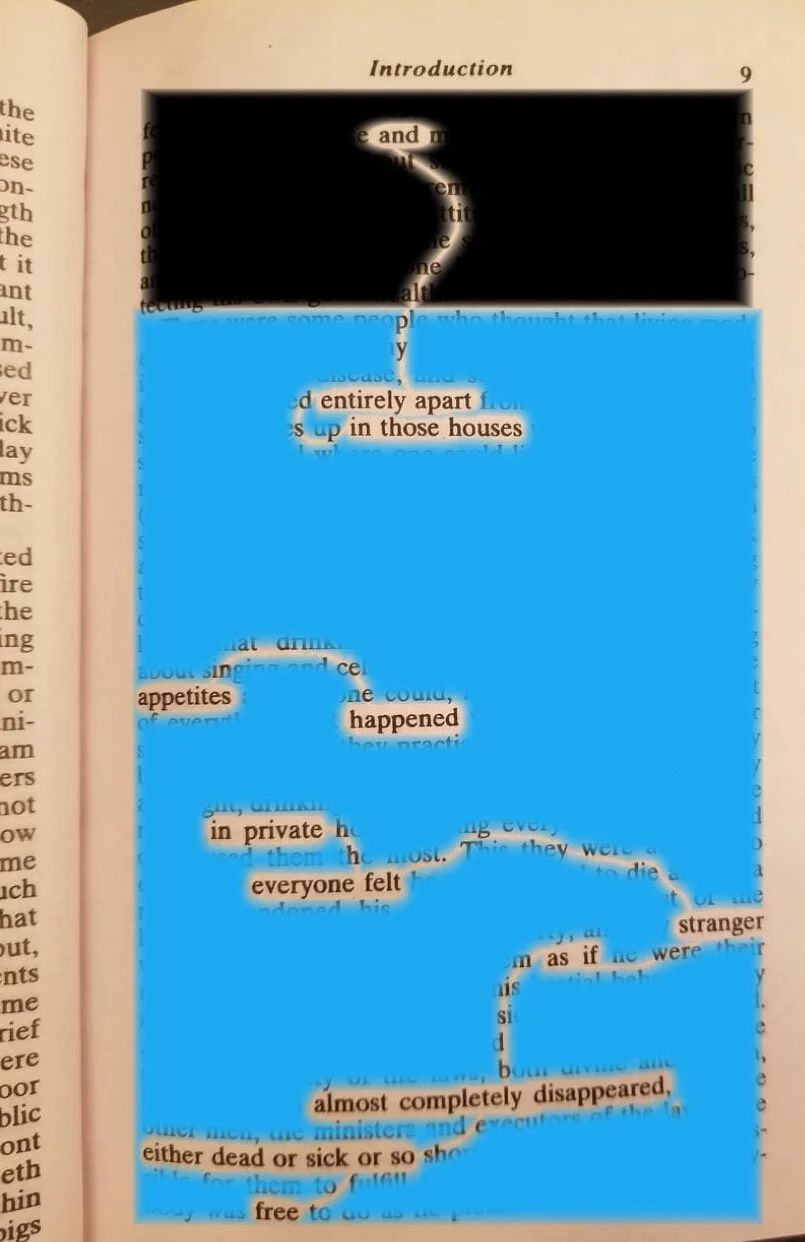

And entirely apart in those houses, appetites happened. In private, everyone felt stranger, as if almost completely disappeared, either dead or sick or so free—

Name touching name, a small mutual solace. Go further. Adhering to which purpose, they jested and laughed—

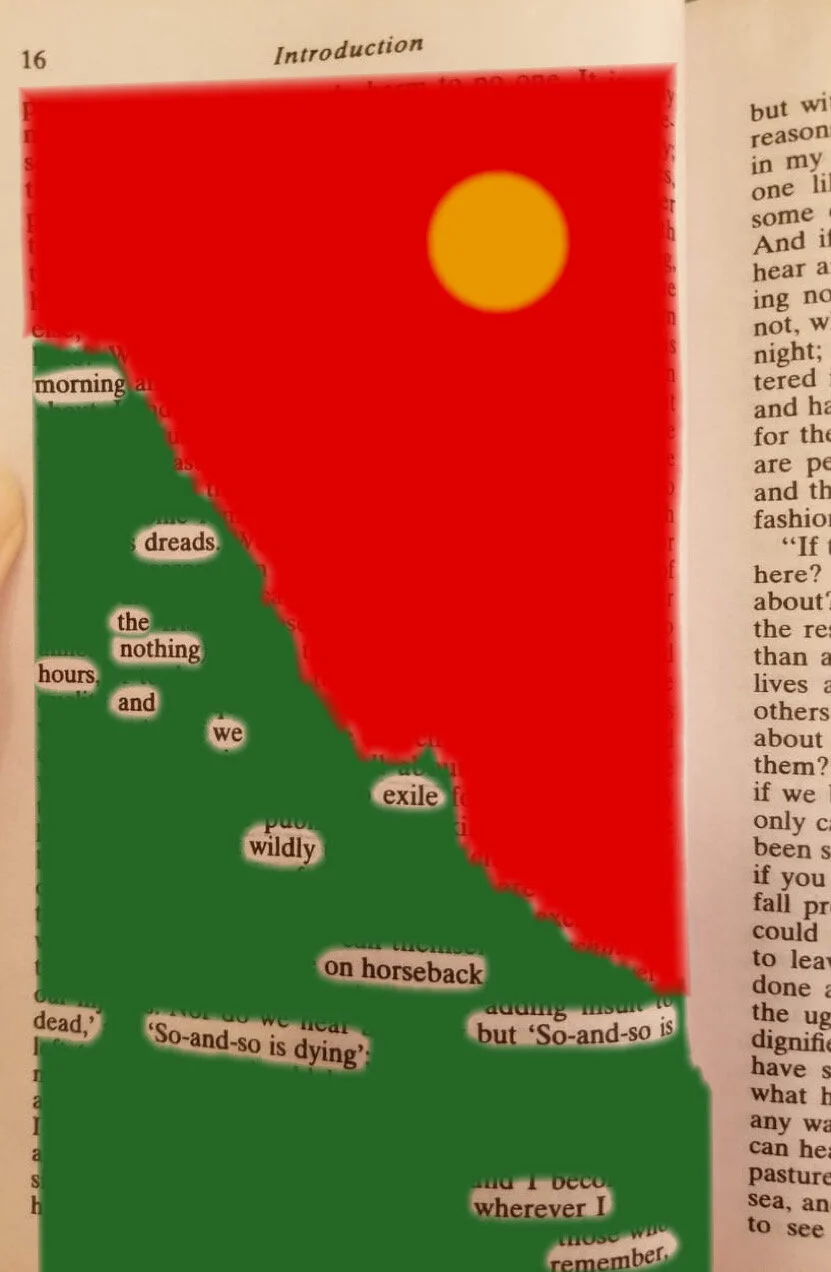

Morning dreads the nothing hours, and we exile wildly on horseback but “So-and-so is dead,” “So-and-so is dying,” wherever I remember—

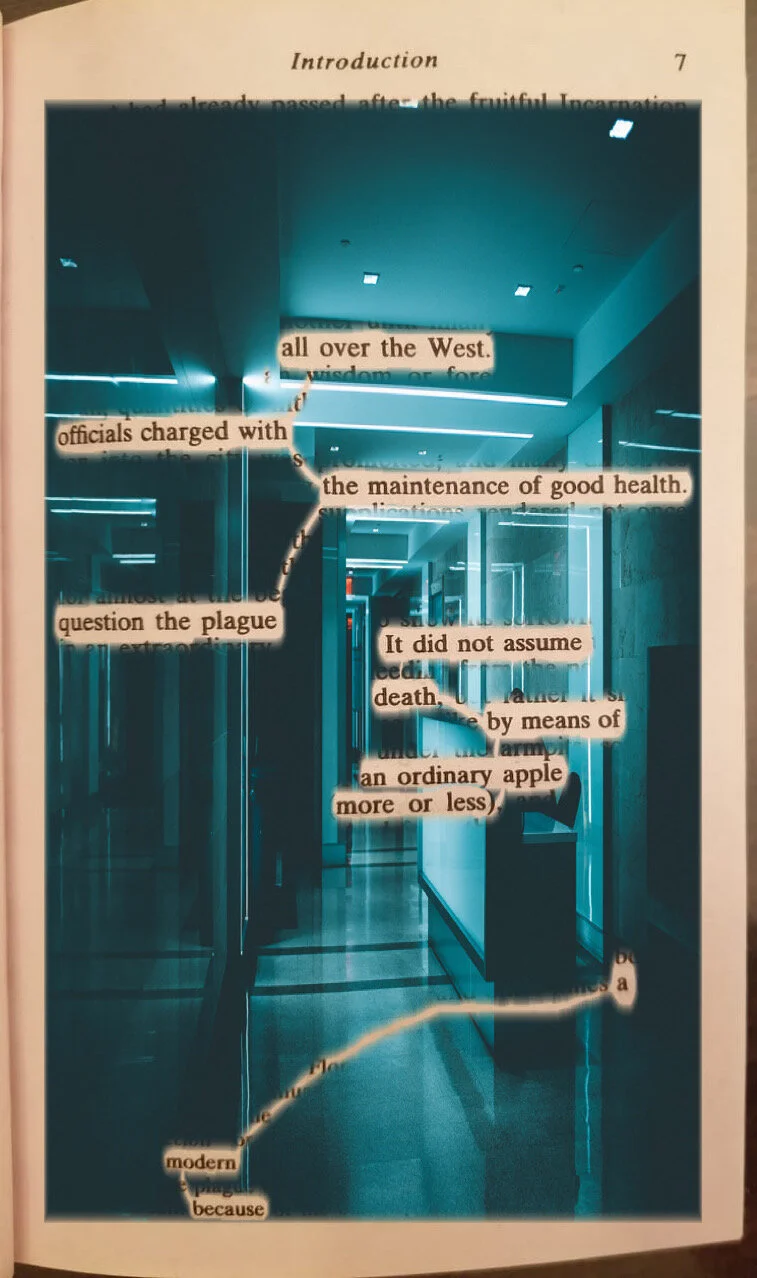

All over the West, officials charged with the maintenance of good health questioned the plague. They did not assume death by means of an ordinary apple, more or less, a modern because—

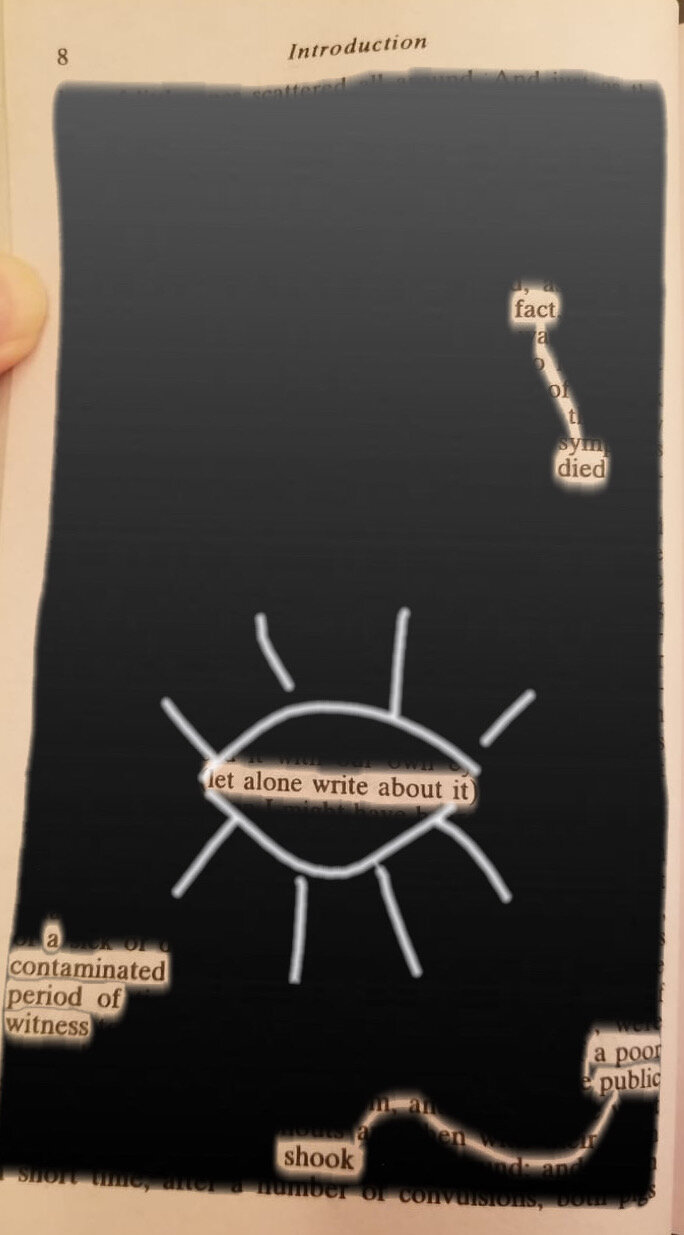

Fact died. A contaminated period of witness. A poor public shook, let alone write about it—

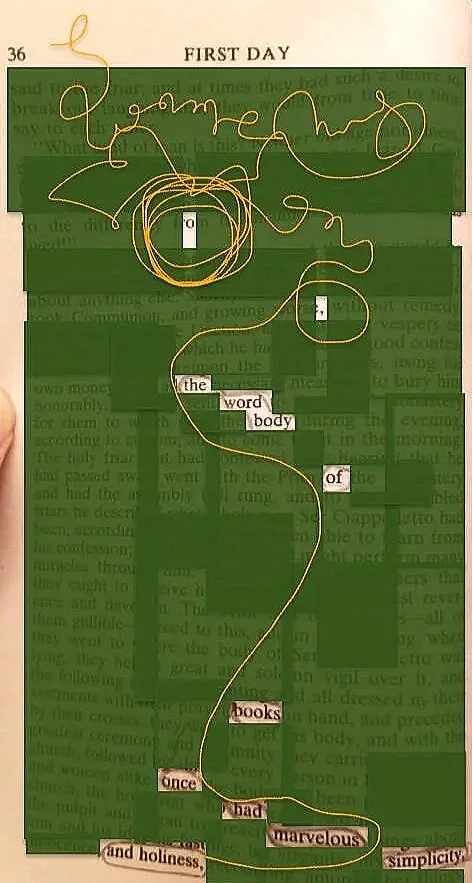

O, the word body of books once had marvelous simplicity and holiness—

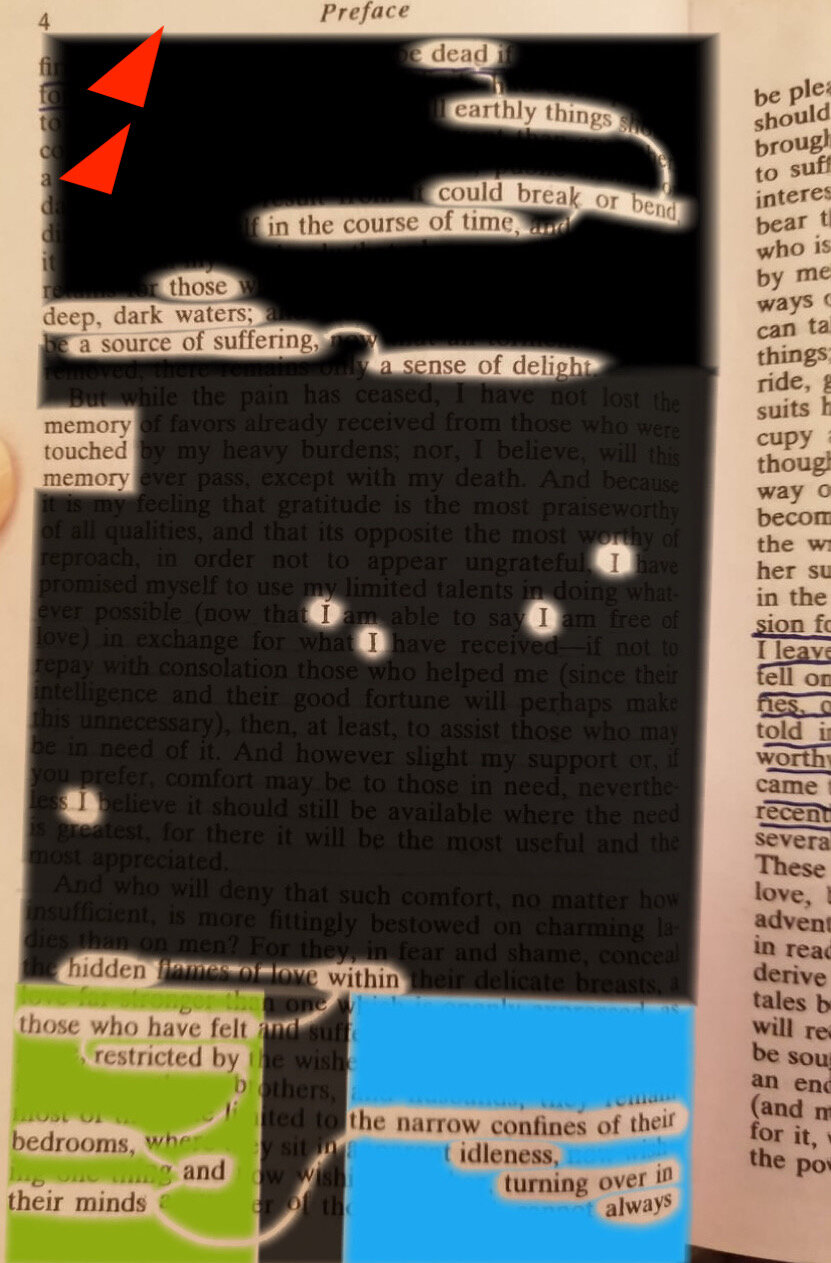

In the course of time, these deep dark waters are a source of suffering and a sense of delight. Memory touched memory. ( I, I, I, I, I ) hidden within those bedrooms and their minds, the narrow confines of their idleness, turning over in always—